Reading "No Longer Human" and "The Stranger" as Eastern and Western Parallels

Left: Osamu Dazai, Right: Albert Camus

I read No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai a while ago. Upon finishing, I felt a sense of déjà vu to another book, The Stranger by Albert Camus. These two novels originated from opposite ends of the world - Japan and France, yet they felt very similar, as if they were the Eastern and Western parallels of each other. Both share an overarching theme of the alienation caused by rejecting society’s conventional ethics: neo-Confucianist East Asian ethics in No Longer Human; and Christian ideals of the miracle of life and salvation in The Stranger.

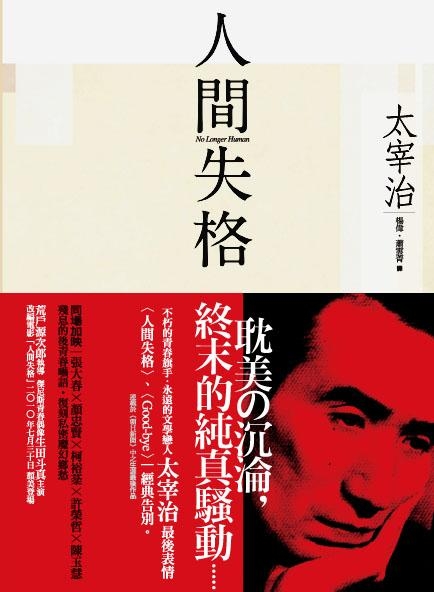

No Longer Human

No Longer Human (original Japanese title: 人間失格), is a novel written by Japanese author Osamu Dazai (太宰 治). It is considered a seminal work among Japanese literature and the second-highest selling novel in Japan of all-time. No Longer Human is also critically acclaimed across East Asia, spawning multiple translations and adaptations. On a personal note, one of my favorite filmmakers, Wong Kar-wai, cited Dazai as a major artistic influence.

No Longer Human was published in 1948, a time when literary censorship had just been lifted and Japanese society was dealing with the aftermath of militarism and the horrors of war. During this period, many authors including Dazai were exploring new ideas and repudiating traditional ones. In No Longer Human, Dazai explores and critiques East Asian ethics which serve as a basis of social conduct in Japanese society.

Post-war Japan, source: AP

East Asian ethics is heavily influenced by neo-Confucianism, a school of thought that emphasizes maintaining societal cohesion (collectivism), and devotion to family elders (filial piety). In the semi-autobiographical No Longer Human, Dazai writes about the protagonist, Oba Yozo in first-person, vividly describing Yozo’s internal thoughts and feelings. Much of Yozo’s experiences were based on Dazai’s own, and much of Yozo’s outlooks likely mirror Dazai’s as well.

People talk of “social outcasts.” The words apparently denote the miserable losers of the world, the vicious ones, but I feel as though I have been a “social outcast” from the moment I was born.

In Japanese collectivist society, every individual has responsibility to maintain societal cohesion above personal interests. A central motif in No Longer Human is Yozo’s struggle to adhere to this responsibility. Yozo initially conforms to collectivism in his youth. He wins the respect of his peers as by becoming top of his class while engaging others through a jovial facade. However, he internally struggles with this facade and views these shallow acts of amicability as “mutual deception”. Looking for solace, he joins an underground political group. However, even within this group, he maintains a guise of conformity by hiding the fact that he disagrees with their political views.

I am convinced that human life is filled with many pure, happy, serene examples of insincerity, truly splendid of their kind-of people deceiving one another without (strangely enough) any wounds being inflicted, of people who seem unaware even that they are deceiving one another.

Over time, Yozo grows increasingly disillusioned as a series of setbacks derails his path to become a productive member of society. He is self-aware and recognizes himself to be unfit for collectivism and starts a life of individualistic hedonism. He begins heavy drinking and later substance abuse; abandons pursuing employment and financial independence from his family; and engages in debaucherous womanizing. All of these acts represent Yozo’s utter rejection of collectivist society.

The rejection of filial piety plays another major role in the novel. Yozo’s father’s relationship with Yozo’s is typically Eastern - one that is perpetually underscored by expectations. He is initially is begrudging obedient and diligently follows his father’s wishes over his own intentions, as when he accepted an unwanted gift or studied to pursue civil service instead of art school.

Eventually however, his hedonistic life causes him to be estranged from his family. Yozo is cut off from financial support and forced to live his own. Yet despite Yozo’s defiance, his father remained a central presence in his life. Upon receiving news of his father’s death, he remarks:

The news of my father’s death eviscerated me. He was dead, that familiar, frightening presence who had never left my heart for a split second. I felt though the vessel of my suffering had become empty, as if nothing could interest me now. I had lost even the ability to suffer.

Yozo’s rejection of collectivism and filial piety leads to a downward spiral of depression. The novel concludes with him becoming fully ostracized from his family and society as he is reclused to an sanatorium. In some of the final lines of the novel, Yozo states:

Disqualified to be a human being. I had now ceased utterly to be a human being.

The context of these lines refer to Yozo’s admittance to the sanatorium, but can also be symbolic of his rejection of collectivism and filial piety. The novel equates these ethics as the basis of human conduct. Yozo’s rejection of these ethics thereby causes his disqualification from humanity.

The Stranger

The Stranger (original French title: L’Étranger) is a novel by French author Albert Camus. Widely praised as a Western literary classic, The Stranger is regarded as Camus’ breakthrough work and marks the start of his Nobel winning literary career. Like No Longer Human, Camus’ critiques and rejects the conventional ethics of his society and time - the Christian ideals of the miracle of life and salvation.

The Stranger was published in 1942 and accounts the story of Meursault, a French Algerian settler. Algiers was the first territory colonized by France as part of its second colonial empire. At the time, France’s justification of the French colonial expansion was to “civilize” other parts of the world through Christianity. Therefore, Christian tradition greatly influenced ethics, philosophy, and social conduct both domestically in France, and in its colonies such as Algiers.

French Algiers, 1910

Christianity views life as a miracle - one of wonder, beauty, and meaning created by a supremely intelligent God. Through faith to God, one can reach salvation, be absolved from sin, and enjoy an afterlife beyond a mortality. In The Stranger, Camus thoroughly rejects this Christian view.

Maman died today. Or yesterday maybe, I don’t know. I got a telegram from the home: “Mother deceased. Funeral tomorrow. Faithfully yours.” That doesn’t mean anything.

Meursault’s first-person narration shows him to be an emotionally-detached character, consistently reacting to poignant events with ambivalence. In the start of the novel, he attends his mother’s funeral, during which he is visibly aloof while others are distraught. When his girlfriend asks if he wanted to marry her, he casually accepts yet readily admits that he probably does not love her. When he kills a man who injured his friend, he does not feel anger, fear, or remorse.

Through the lack of any emotional response, Meursault’s life is depicted as a series of events of the same emotional importance. To Meursault, these momentous events of death, love, and murder are equivalent to talking to another patron at a diner or an afternoon on the balcony. This outlook strips away significance from life’s events, rendering life to be inconsequential and random - contradicting the Christian idea that life is miraculous and meaningful.

The novel’s turning point is when Meursault’s murder of an Arab man. The victim is unnamed, showing the disregard and superiority the settlers had over the natives. The man had injured one of Meursault’s friends, yet Meursault does not attribute his motivation to vengeance, but rather a whim caused by the summer heat.

I realized then that a man who had lived only one day could easily live for a hundred years in prison. He would have enough memories to keep him from being bored. In a way, it was an advantage.

This crime leads to his imprisonment and trial. Meursault initially laments his loss of worldly pleasures, but quickly adapts to austerity in confinement. The defense attorney is initially convinced that the sentence will be light and hints Meursault to show remorse to the prosecution. However, Meursault does not attempt to make a case for himself, matter-of-factly stating his aloofness. As a result, he is sentenced to death, a sentence which he does not argue.

A chaplain visits him prior to his execution to convince him to follow God in order to reach the afterlife. However, for the first time in the novel, Meursault shows emotion and angrily rebuffs the chaplain in a violent rage. He screams to the chaplain that nothing mattered in life and only certainty was that everyone was condemned to die.

Meursault’s acceptance of his sentencing and rebuff of the chaplain represent a rejection of salvation, in both the mortal and the Christian sense. He does not believe in the value of his life or the afterlife. This is further emphasized by the irony that the first time Meursault shows emotion in the novel is when rebuffing the chaplain, who is symbolic of the Christian faith. As Meursault is about to be executed, he remarks:

As if that blind rage had washed me clean, rid me of hope; for the first time, in that night alive with signs and stars, I opened myself to the gentle indifference of the world. Finding it so much like myself - so like a brother, really - I felt that I had been happy and that I was happy again.

Throughout the novel, Camus indirectly rejects the Christian tradition by presenting life to be meaningless and random. This rejection then is highlighted through the violent encounter with the chaplain. This set of ideas led to the philosophical movement of Absurdism, which resonated Europeans in the early 1900s, during a period marked by seemingly meaningless and random wars.

Conclusion

In No Longer Human, Yozo rejects Eastern society’s conventional ethics of collectivism and filial piety. As a result, he is alienated from society and sent to a sanatorium. In The Stranger, Meursault rejects Christian society’s conventional ideals of salvation and miracle of life. As a result, he is alienated from society through imprisonment and execution. Both novels present the shared theme of rejection of a society’s conventional philosophies and ethics, and resulting in a subsequent alienation.

Yushima Seido Confucian Temple in Japan and Reims Cathedral in France

One point of difference is - Eastern ethics are a set of principles which can be followed to varying degrees; while Western Christian ethics represent a binary choice where one either accepts salvation or rejects it. This is symbolized through the two protagonists, where Yozo’s ethical adherence is nuanced and his resulting alienation is a gradual sequence of events, while Meursault’s rejection of Christian ideals is concrete and his resulting alienation is a singular decisive trial.

In the final parts of the novels, Yozo is deeply unhappy with his fate and laments society for being the way it is, while Meursault is satisfied, acknowledging that he “had been happy and (…) was happy again”. This could be due to Yozo feeling a lifelong internal dissonance between himself and society while Meursault freely lives to his principles and readily accepts the consequences. This possibly mirrors Dazai and Camus’ own personal sentiments; Dazai lived a deeply troubled life while Camus was generally happy.

No Longer Human and The Stranger present an elucidating parallel between Eastern and Western societal values. For those looking to further their understanding of Eastern and Western philosophies and ethics, reading these two novels as a pair may broaden your horizons.