Lambda Architecture: A Practical Example

Many tech companies utilize something called Lambda architecture as the basis of their data processing infrastructure, which processes the data needed to drive their most critical business decisions and initiatives.1

This post seeks to explain the what, why, and how of Lambda architecture using a practical example.

The Start

Suppose we are the engineering team of a startup company, making a mobile game. Every morning, Bob, the CEO, will ping us on Slack:

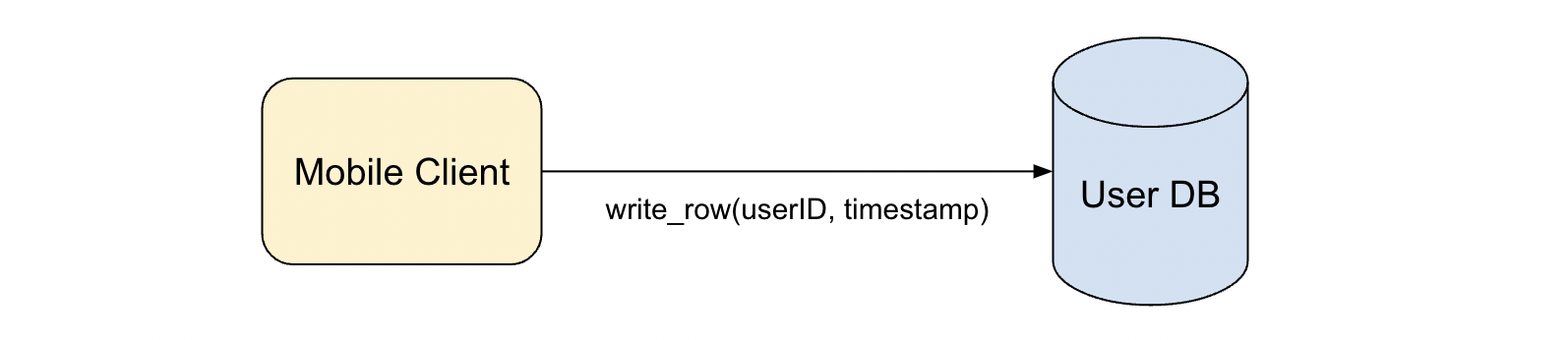

We have a simple architecture where, upon game launch, our game client will log the player’s user ID and timestamp to our SQL database.

To reply to Bob, we run this query:

SELECT COUNT(DISTINCT player_id)

FROM player_table

WHERE DATE(`timestamp`) = DATE_SUB(CUR_DATE(), INTERVAL 1 DAY)

Note, a user can open the game multiple times per day, the COUNT DISTINCT is necessary to get the total unique count

Great, the query runs successfully and we reply to Bob - “21,367 players!”

This architecture is initially scalable enough for our relatively small player-base. Slowly however, our game becomes a massive hit and explodes in popularity. We gain millions of players worldwide and are very excited about the potential of continued growth.

Unfortunately, our SQL database begins to buckle under the increased load. The CPU spikes to 100% and reliability drops - we begin losing data. To support this load, we consider renting more powerful SQL nodes (vertical scaling) and sharding our database (horizontal scaling). However, we do some back-of-envelope calculations and realize either approach would lead to prohibitively expensive infrastructure costs to support the scale we need.

We decide to build a more robust alternative.

Batch Layer

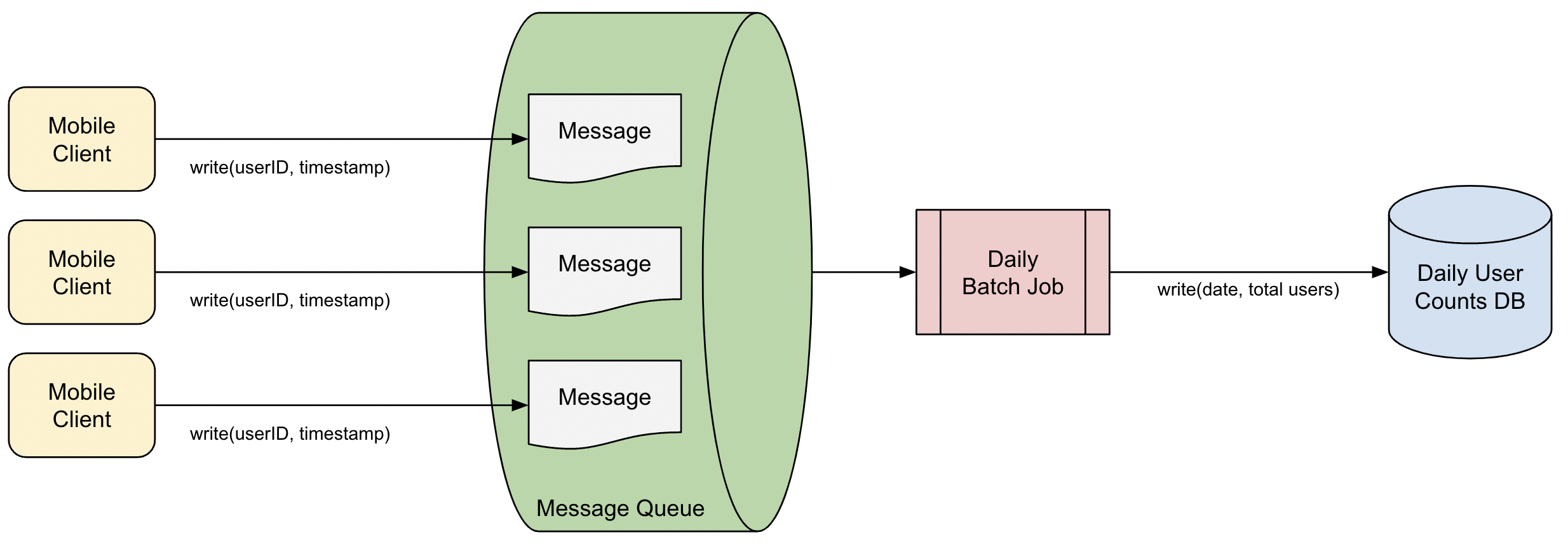

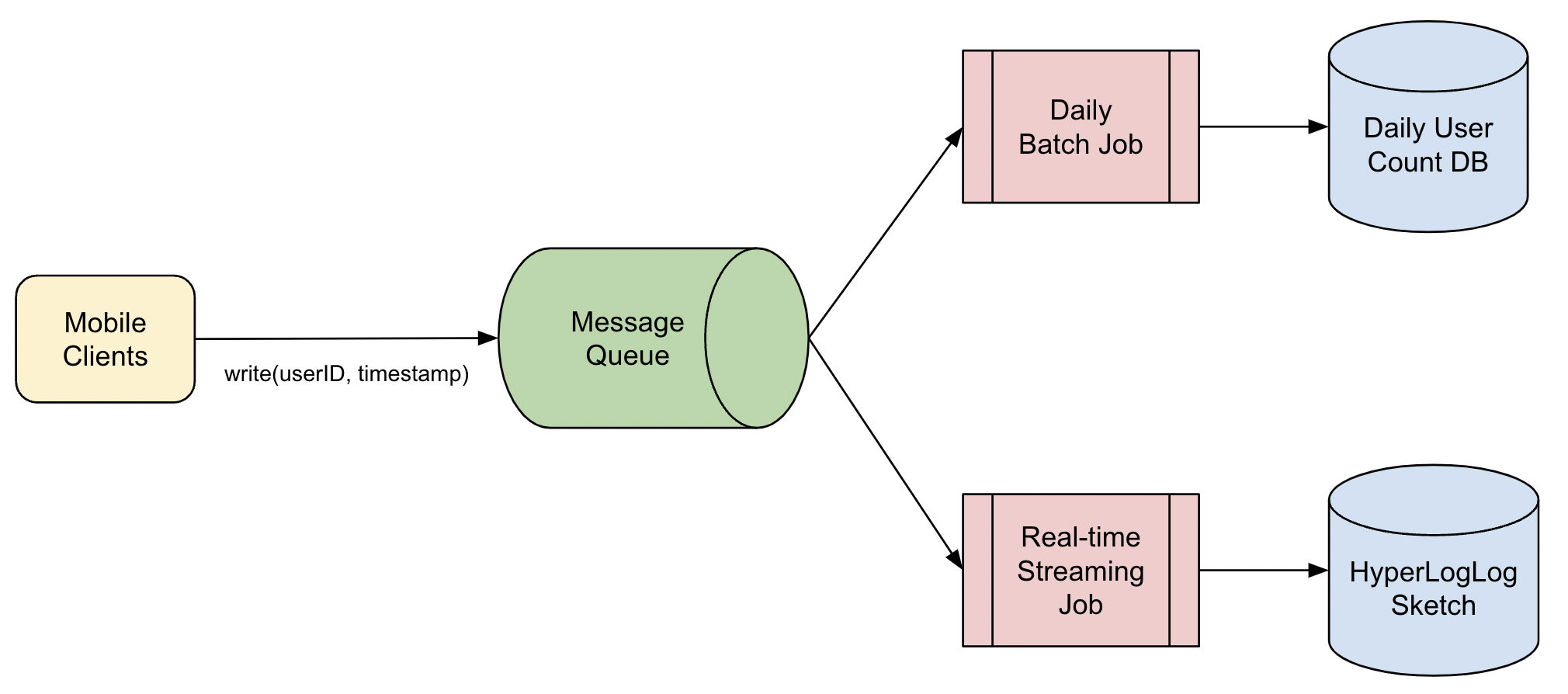

To handle our increased request volume, we need a more efficient way to log the user IDs and timestamps. We decide to write to a message queue instead, which can efficiently support a high number of write requests.

After we write to the message queue, we still need a way to calculate the number of unique players per day. We decide to implement this with a batch MapReduce job. At the end of each day, our job reads all messages written in the previous day in parallel, counts the unique user IDs (de-duplicating as necessary), and writes the result to a DB. The job takes a few hours to complete and the results should be ready by morning.

To further optimize on storage costs, we introduce data retention by regularly purging stale data used already by previous daily jobs from the message queue.

We test and deploy the system, add some metrics and alarms, and go to sleep. The next morning, we wake up to a familiar message from Bob the CEO:

We check yesterday’s job and saw it completed. We query the result and reply to Bob - “20,340,911 players!”

Our system works as expected and the number of players continue to grow, life is good.

Real-time Layer

One day, we get a different Slack message from Bob:

However, we only have the numbers from yesterday. We quickly trigger a manual run of the batch job for today’s data. After few hours when the job completes, we reply to Bob with the number. However, Bob has already ended his workday and is offline.

To be able to handle future questions like this quickly, we decide to build a real-time system. We briefly reconsider our previous design of a SQL DB which can be quickly queried, but remember the scaling constraints. We also consider running the batch job every few minutes to always have up-to-date data, but the batch job is expensive and we can only afford a few runs per a day.

We recall learning about data streaming and how it can be used to handle real-time data, and decide to build a streaming job. We set up our streaming job, and add it as an additional consumer to our message queue where it constantly fetches the latest user IDs from the queue.

We consider outputting the streaming job as to a set of unique user IDs to keep track of the distinct count, but that would require memory proportional to the number of players - too expensive. Since Bob is fine with just a rough number in real-time, we decide to use a probabilistic cardinality counter, such as HyperLogLog which can approximate the number of uniques to a high degree of accuracy at a fraction of the memory footprint.

After deploying the streaming job and HyperLogLog counter, we are now ready to answer Bob’s question quickly at anytime during the day.

Serving Layer

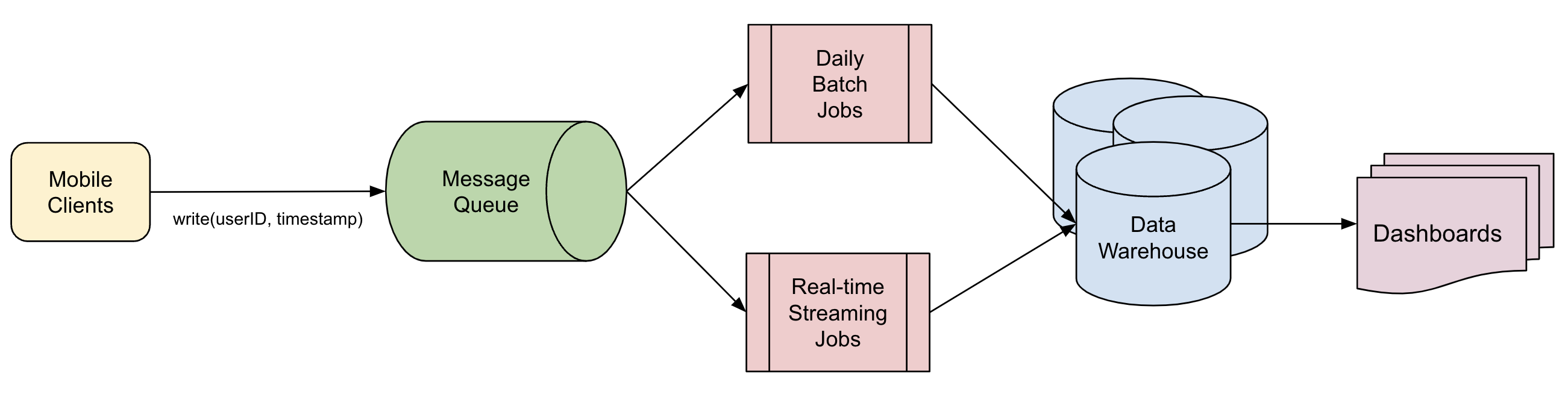

Our game continues to increase in popularity, and both our batch and real-time systems continue to scale successfully. Over time, more business use cases are added such as: How many matches are played per day? How many players per country? How many advertisements shown per hour? etc.

Bob also grows the company by hiring data analysts and forming a business team. As a result, we need a more efficient way to serve the data to them instead of manually running queries and replying over Slack.

We decide to build a serving layer. We join the different databases we have behind a single interface, and build tools and dashboards so the business team can visualize the data and run reports on an ad-hoc basis.

After deploying the serving layer, everyone in the company is now able to access their relevant data.

Conclusion

The batch layer provides accurate data with increased latency - useful for scenarios that require precision over speed (e.g. financial reporting); the real-time layer provides approximate data at a low latency - useful for scenarios that require speed over precision (e.g. operational real-time decision-making). The serving layer enables stakeholders to easily access this data.

These systems form Lambda architecture. This architecture is flexible and powerful, and is used by many tech companies to process the data they need to drive their most critical decisions and initiatives. Although this post described the architecture and tradeoffs at a high level, in a real production environment there are many more considerations, including:

- Scalability: How can I architect this system to scale to my business needs? How do I minimize cost in this system?

- Consistency: How do I know my data is correct? How do I know if it is up-to-date? Is my data ordered in the correct sequence?

- Fault Tolerance: Is my data durable? What kind of guarantees can I provide about my data?

- Operational: How available is my system? How much effort does my team need to ensure its availability?

Additional Resources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lambda_architecture

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MapReduce

- https://databricks.com/glossary/lambda-architecture

- https://www.confluent.io/learn/batch-vs-real-time-data-processing/

-

not to be confused with lambda functions or AWS Lambda/serverless ↩